Recently, I found a few interesting articles/posts that all defend model simplicity.

An interview with Gregory matthews and Michael Lopez about their winning entry in the Kaggle’s NCAA tournament challenge “ML mania” suggests that it’s better to have a simple model with the right data than a complex model with the wrong data. This is my favorite quote from the interview:

https://twitter.com/lauramclay/status/496710473614909440

John Foreman has a nice blog post defending simple models here. He argues for sometimes replacing a machine learning model for clustering with an IF statement or two. He links to a published paper entitled “Very simple classification rules perform well on most commonly used datasets” by Robert Holte in Machine Learning that demonstrates his point. You can watch John talk about modeling in his very informative and enjoyable hour-long seminar here.

A paper called “The Bias Bias” by Henry Brighton and Gerd Gigerenzer examines our tendency to build overly-complex models. Do complex problems require complex solutions? Not always. Here is the abstract.

In marketing and finance, surprisingly simple models sometimes predict more accurately than more complex, sophisticated models. Why? Here, we address the question of when and why simple models succeed — or fail — by framing the forecasting problem in terms of the bias-variance dilemma. Controllable error in forecasting consists of two components, the “bias” and the “variance”. We argue that the benefits of simplicity are often overlooked by researchers because of a pervasive “bias bias”: The importance of the bias component of prediction error is inflated, and the variance component of prediction error, which reflects an oversensitivity of a model to different samples from the same population, is neglected. Using the study of cognitive heuristics, we discuss how individuals and organizations can reduce variance by ignoring weights, attributes, and dependencies between attributes, and thus make better decisions. We argue that bias and variance provide a more insightful perspective on the benefits of simplicity than common intuitions that typically appeal to Occam’s razor.

What about discrete optimization models?

All of these links address data science problems, like classifying data or building a predictive model. Operations research models are often trying to solve complicated problems with a lot of constraints and requirements. They have a lot of pieces that need to play nicely together. But even then, it’s often incredibly useful to ask the right question and then answer it using a simple model.

I have one example that makes a great case for simple models. Armann Ingolfsson examined the impact of model simplifications in models used to locate ambulances in a recent paper (see citation below). Location problems like this one almost always use a coverage objective function, where locations are covered if an ambulance can respond to the location in a fixed amount of time (e.g., 9 minutes). The question is how to represent the coverage function and how to aggregate the locations, two choices of model error. The coverage objective function can either reflect deterministic or probabilistic travel times. Deterministic travel times lead to binary objective function coefficients (an ambulance covers a location or is doesn’t) whereas probabilistic travel times lead to real-valued objective coefficients that are a little “smoother” with respect to distances between stations and locations (an ambulance can reach 75% of calls at this location in 9 minutes).

This paper examined which is worse: (a) a simple model with highly aggregated locations but realistic (probabilistic) travel times or (b) a more complex model with finely granulated locations but less realistic (deterministic) travel times.

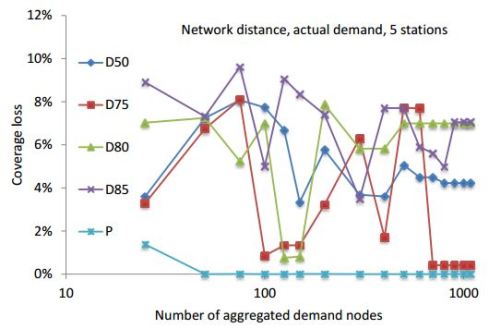

It turns out that the simple but realistic model (choice (a)) is better by a long shot. Here is a figure from the paper that reflects the coverage loss (model error) from different models. The x-axis reflects aggregation, and the y-axis reflects coverage loss (model error, more is bad). The different curves reflect different models. The blue line is the model with probabilistic travel times; the rest have deterministic travel times with the binary value determined by different percentiles.

From the paper: “Figure 4 shows how relative coverage loss varies with aggregation level (on a log scale) for the five models, for a scenario with a budget for five stations, using network distances, and actual demand. This figure illustrates our two main findings: (1) If one uses the probabilistic model (THE BLUE LINE), then the aggregation error is negligible, even for extreme levels of aggregation and (2) all of the deterministic models (ALL OTHER LINES) result in large coverage losses that decrease inconsistently, if at all, when the level of aggregation is reduced”

From the conclusion:

In this paper, we demonstrated that the use of coverage probabilities rather than deterministic coverage thresholds reduces the deleterious effects of demand point aggregation on solution quality for ambulance station site selection optimization models. We find that for the probabilistic version of the optimization model, the effects of demand-point aggregation are minimal, even for high levels of spatial aggregation.

Citation:

Holmes, G., A. Ingolfsson, R. Patterson, E. Rolland. 2014. Model specification and data aggregation for emergency services facility location. [Supplement] [Submitted, last revision March 2014.]

What is your favorite simple model?

Related posts:

August 12th, 2014 at 8:08 am

Hear! Hear! I cringe whenever I see two-page MIP formulations.

On a somewhat related note, Wisconsin’s own Elliot Sober* has some interesting papers** on parsimony in philosophy of science.

*http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elliot_Sober

**http://sober.philosophy.wisc.edu/selected-papers

August 12th, 2014 at 1:41 pm

Great post. I have also seen that complicated optimization models can be difficult in practice because the user have too many parameters to adjust and difficulties understanding why it produce the solutions it does.

August 12th, 2014 at 4:28 pm

In both their Intro and Elements books, Hastie, Tibishrani and Friedman make a very great many references to the fact that in statistical and machine learning it isn’t just Bias and Variance that you trade off, but more often Bias, Variance, and Interpretability.

More researchers and many professionals could probably do with a sign over their monitor reminding them of that!

August 12th, 2014 at 7:13 pm

Occam’s Razor.

I think whether to use a simple model or a complex one should depend upon the context. If your boss asks you a yes or no question about whether his plan is going to work out, an answer with percentage will not make him happy.

September 9th, 2014 at 7:22 am

[…] In Defense of Model Simplicity: Examples from Laura McLay about problems in data science and optimization that respond better to a simple model than a complex one. […]

September 21st, 2014 at 4:01 am

Hi Laura, yet another blog supporting your defense

http://www.scdigest.com/experts/DrWatson_14-09-11.php?cid=8481

September 22nd, 2014 at 6:06 am

Like Einstein said, “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler”. Notice the “but not simpler”.

Consider these 2 counter examples:

– VRP with air distances loses 5% compared to real-world distances

– Flaw of averages: When you’re going to sell between 50k and 150k, its not ok to tell your boss it’s 100k.

In both cases, simplification is bad.

I am all in favor of simplifying tooling, but be carefull with simplifing business use cases…

September 22nd, 2014 at 6:07 am

Link for flaw of averages:

http://www.stanford.edu/~savage/flaw/Article.htm

September 22nd, 2014 at 6:07 am

Link for VRP air distances:

http://www.optaplanner.org/blog/2014/09/02/VehicleRoutingWithRealRoadDistances.html